“Your teacher covered that last year” or “this semester we will cover” still rankles my professionalism as a teacher. Teaching for coverage means nominal teaching and learning. It means spending the least amount of time engaged in teaching and learning for the sake of topical accountability. Coverage teaching is like the proverbial river that is a mile wide and an inch deep – it emphasizes breadth without depth. In my naivety as a young educator I believed that if something was worth teaching it was worth learning well and that meant deeper teaching and learning. Conversely, why waste time and energy on teaching things we did not plan for children to learn well? I still believe this.

Years ago when I heard my principal or district curriculum leader talk of coverage, I assumed they were generalizing about the amount of information in any grade level of our social studies curriculum and the finite amount of instructional time in an academic year. But they weren’t. “You can’t teach everything in your curriculum with the same level of intensity” I was told. “So, cover it all.” It took me a long and troublesome time to understand this, however understanding did not mean accepting it.

There is a line between coverage and knowing and understanding.

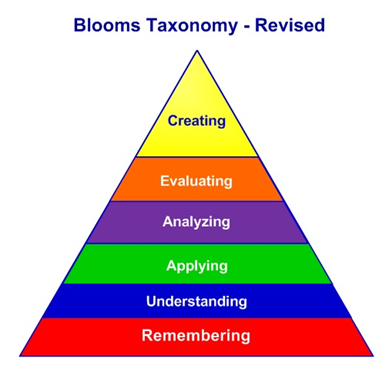

Early on in teacher training, we are taught Benjamin Bloom’s Taxonomy. In the 1950s Bloom established six levels of thinking, learning, and understanding with labeling that helps us explain a rationale for teaching and learning designs. Seventy years later, I still like how Bloom helps me to add depth to the “wide river” of information we teach. The model below shows a revised taxonomy – the terms have been modified from Bloom’s original for clearer explanation of the cognitive levels.

bloom’s taxonomy revised – Higher order of thinking

Although there is a vertical dimension to the taxonomy, Bloom did not intend for all teaching to involve all six levels. Curriculum planners use the levels as goals for teaching and learning. Some learning, in fact most of what we learn, is meant to be at the remembering/understanding level of usage. Other learning is meant to be scaffolded into a variety of applications, or to inform careful analyses, or to evaluate options and opportunities, and to create original work. Though it looks like a ladder, a user does not use every rung to engage in higher order cognition. Instruction and learning can scaffold from understanding to analyzing, or evaluating, or creatin.

Coverage teaching is the act of “mentioning” without the explicit intention of remembering. There is a lot of mentioning in education. Synonyms for mentioning cause us to smile and acknowledge that teachers mention without teaching. When a teacher “alludes to, refers to, touches upon, hints at, speaks about briefly, broaches or introduces only,” that is mentioning. Children may or may not hear or read what a teacher mentions as an aside. Things that are mentioned are characterized as “things it is nice to know but it is okay not to know.” Like, the value of pi is abbreviated to 3.14. As an irrational number, Pi can be calculated out to an infinite number of numbers but who cares? A math teacher covers or mentions that fact but directly instructs that the usable value of pi is 3.14. Best practice does not include “mentions” in assessments of student learning, although there is a lot of bad practice in the field.

Coverage may be all the questions on Jeopardy that sound somewhat familiar but just will not come to mind.

I think of coverage as the blank space below the bottom of Bloom’s taxonomy; it is the noise in the world we are not intended to remember.

Remembering and understanding is the meat and potatoes of most teaching. The information – facts, data, concepts, generalizations, and skill sets we want children to know, we teach with high intention. In the language of backward design, if we intend to test children on something, we intend to teach it well so that it will be remembered and understood.

Direct instruction is one of many teaching strategies most often used when we teach for remembering and understanding.

Children learn the alphabet and numbers, sight words and number facts early as foundational knowledge. In school we use direct instruction to drill and practice and ensure memory of these. Retention theory drives our teaching for remembering – we use immediate drill and practice/repetition to strengthen short-term memory and interval practice over time to ensure what is learned is retained and recalled in long-term memory. In a spiraled social studies curriculum, we teach US History in elementary, middle school, and high school because we want all children to know their national stories. Repetition and elaboration cause remembered learning.

Remembering is a student’s identical retelling of information or identical demonstration of what was taught. We require correct and complete retelling.

Understanding is explaining what was taught with fidelity in the student’s own words and doing the skill with fidelity in the student’s own style. Understanding is using what is remembered and making an inference about it or summarizing it in simpler language or combining several pieces of information into meaningful statement that keeps the significance and essence of what is being combined.

There also is a line between knowing and understanding what we learn and the rest of Bloom – what comes next is the so what of education.

Separating the noise of information from the teaching of remembering and understanding, gets us to the “so what” levels of Bloom where what was learned is applied, analyzed, evaluated, and built upon creatively. These four Bloom levels give us the rationale for why teaching for remembering and understanding are such a large part of our school calendar. Without foundational memory about stars, planets, moons, suns, constellations, galaxies, and a universe(s), nothing we see in the sky above us would make sense. Space would just be space. Lifesaving surgery would be butchery. Agriculture and manufacturing would just be guessing work.

Other teaching strategies become available when students have a knowledge and understanding of foundational information and skills. I use the C3 Framework for social studies as an example of instructing above the remembering and understanding line. C3 (College, Career, Civic Life) uses an inquiry process for students to investigate, expand and integrate their knowledge of civics, economics, geography, history, and the behavioral sciences.

“The C3 Framework, like the Common Core Standards, emphasizes the acquisition and application of knowledge to prepare students for college, career, and civic life. It intentionally envisions social studies instruction as an inquiry arc of interlocking and mutually reinforcing elements that speak to the intersection of ideas and learners.” C3 uses “questions to spark curiosity, guide instruction, deepen investigations, acquire rigorous content, and apply knowledge and ideas in real world settings…”

https://www.socialstudies.org/standards/c3

This is not coverage teaching!

Parallel to C3, curricula in every school subject, from art to woodworking, builds upon information and skills students learn at the remembering and understanding levels of instruction. The front of a refrigerator in most student homes is covered with student drawings and finger paintings. Over time, shelves and walls display how student application of basic information and skills blossoms into more intricate and sophisticated art. Student art displayed in local galleries, libraries, and art shows illustrates how student artists apply of fundamental concepts and skills, analyze and interpret subjects, and create new and original art.

Tech ed students manufacture, ag students grow and cultivate, computer science students program and engage in robotics, ELA writers craft poems and stories, and marketing ed students create businesses, apply accounting, create and manage product, lead and supervise personnel in the pursuit of economic growth. Once students know and understand, they can pursue their personal interests for a lifetime.

Know and be the difference.

There is so much in a teacher’s annual curriculum and so little time that it is easy to fall into the coverage mode of teaching. But why? In today’s world, coverage learning is what any child can achieve using Google or AI.

Two centuries ago, teachers were the source of information and applied learning. A century ago, students could read books for information; it was teacher directed and interpreted learning that moved children to young adults ready for college or work. Today, information sources abound, so much so that it hard to know information from noise. Today it takes a teacher to forge information into memory and understanding. And it takes a teacher to guide, monitor, and mentor how students illustrate and expand their learning. Well-conceived and instructed learning remains a springboard for life’s successes.

There is no time or place today for coverage teaching.