“I taught a lesson to my students. They should have learned it.”

Some students learned “it”, and some did not. And some tuned out and were not mentally present for learning. Walk the hallways of any school. Stop to look in and watch the teaching and learning act in motion. We see the teaching. We assume the learning. At the end of any lesson, we may hear the teacher sigh with this assumption. “There. I taught it. They should have learned it”. Or was it exasperation.

What do we know?

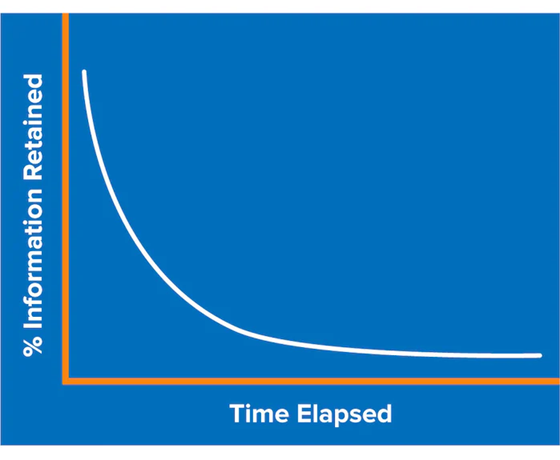

We don’t remember all that we are taught for very long. This is a fact. Hermann Ebbinghauss, a German psychologist, explored memory and why we forget. His work in the 1880s has been replicated and validated over time. His “forgetting curve” is instructive today.

“We forget 50% of the new information we are presented within 24 hours and 90% of that new information within a week.”

Perhaps the above statement should be emblazoned on the back wall of every classroom for teachers to constantly read as they teach.

https://www.mindtools.com/a9wjrjw/ebbinghauss-forgetting-curve

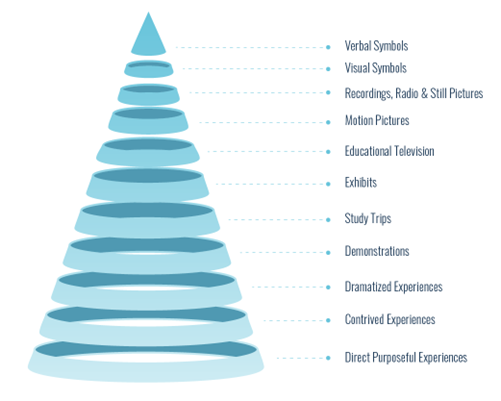

Ebbinghauss’ “forgetting curve” corresponds with Edgar Dale’s “Cone of Experience”. In the 1960s Dale posited what he called the “Cone of Experience”. Dale examined how people receive information. He developed a model portraying the effectiveness of the mode for presenting new information and memory. The isolated act of reading was the least effective while designing and making a presentation was the most effective.

Later, misinterpreters of Dale’s work relabeled it the “Cone of Remembering” and this misinterpretation has been repeated until many believe it as factual. This is the misinterpretation.

WE REMEMBER

10% of what we read.

20% of what we hear.

30% of what we see.

50% of what we see and hear.

70% of what we discuss with others.

80% of what we personally experience.

95% or what we teach others.

This is Dale’s Cone of Experience.

Presentation modes of verbal and visual symbols (words and graphics) are impersonal and less well remembered while the four experiential activities at the bottom of the cone require personal engagement and result in better retention.

https://uh.edu/~dsocs3/wisdom/wisdom/we_remember.pdf

Ebbinghauss and Dale inform us that memory is fickle and short-lived if it is isolated and left alone.

Capitalize on learning and make it memorable.

Further, Ebbinghauss’ research tells us that we can reduce the decline of memory by using several instructional strategies. He found these to reduce forgetting.

- Reinforce content, skills, and dispositions about learning regularly. We know from retention theory that if we want information or skills to be accessible in short-term memory, students need 5-7 repetitions of mentally or physically working with they are to remember. Theory tells us that 18 – 20 repetitions are required to create long-term retention. If the biggest loss of memory is within one day, repetition must be at least daily to begin building memory. This clearly is Ebbinghauss.

Consider automaticity of math facts. We teach and drill children to learn addition, subtraction, multiplication and division math facts in the primary grades. Then in the upper elementary and middle level grades we assume these facts are secured memory for all students. In fact, they are not. If we want to ensure automaticity, repeat episodes of the several times every year. Make a game of it but do it. Assumptions that children remember almost always leads to problems.

- Presentation matters for clarity of what is to be remembered. Make the new information easier to comprehend and absorb. Assign smaller chunks of material to be read or watched. Use visuals and graphics to assist students to make a clearer understanding of new information. Build outlines, maps, and graphic organizers for students to link new information to what they already know. This clearly is Dale.

https://www.lucidchart.com/blog/types-of-graphic-organizers-in-education

- Make learning relevant and personal. Motivation theory tells us that when students see themselves using new information or skills, they are more receptive to new learning and invested in remembering it. Personalizing new learning gives students a purpose for learning and remembering it.

- Make learning active not passive. Use as many modalities for students to engage with new learning as are reasonable. Approach new learning verbally – say it, write it, interpret it in a different language. Approach it creatively – draw it, paint it, sculpt it, build it, sign it, and act it out. Be careful not to let the projection of new learning become more important that the new learning itself.

https://asc.tamu.edu/study-learning-handouts/using-learning-modalities

What to do – Teach it, Teach it better, and Teach it again and again.

Teach less. A grade level or subject area curriculum always contain more learning than can be accomplished within the confines of school year. A teacher who says, “I taught everything in my curriculum or course guide” either has Cliffs Notes as a guide or is settling for very minimal student achievement in the end of year assessments. This is not a license to discard a curriculum or course guide, but to carefully select the essential content information, skills, and dispositions that all students must learn and remember. Both words are critical – learn and remember.

Teach it better. Use sound theories of instruction to build student retention and use of what they learn. Chunk new learning for clarity. Provide organizers of connecting new to secured learning. Use multiple examples to help challenged learners find a connection to new learning. The use of sound theories to teach essential new learning by itself will propel student achievement.

Make it meaningful. Attach new learning to what students already know. Attach new learning to the interests of the students, their families, and their community. Attach new learning to what students will be learning and doing in their educational and career futures. Once a child finds a purpose for learning, get out her way and simply coach her along the way.

Teach it again and again. We parse our curriculum into units and chapters and almost never reteach or return to a unit or chapter once we complete it. Then we wonder why students at the end of the year cannot recall with completeness or clarity what they learned at the beginning. Take the time to repeat a chapter review from several chapters ago. Check to know what students remember and can to with completeness and clarity. If that knowledge or skill is essential, teach it again. Do this rear-view mirror chapter review throughout the year. You will see better student performances on end of year tests and future teachers of your students will be amazed at their longer-term memory.